A rumination in concepts of cosmic comfort and conviction crises, drawing back to the literary philosophies of H. P. Lovecraft and moving forward with those of Ukrainian-Brazilian writer Clarice Lispector. Authored by Nilani Mathur.

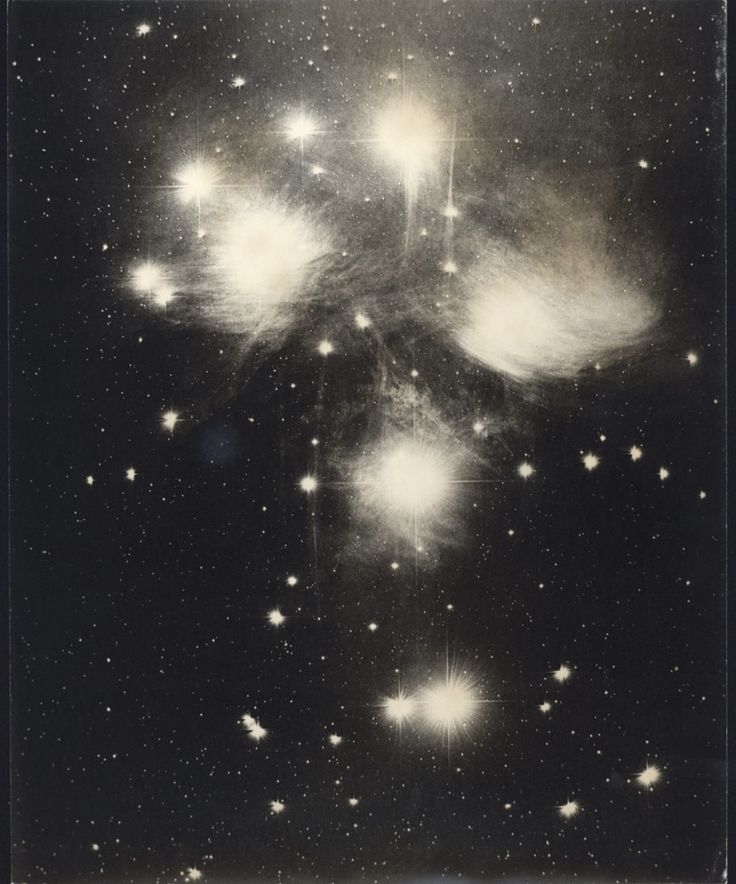

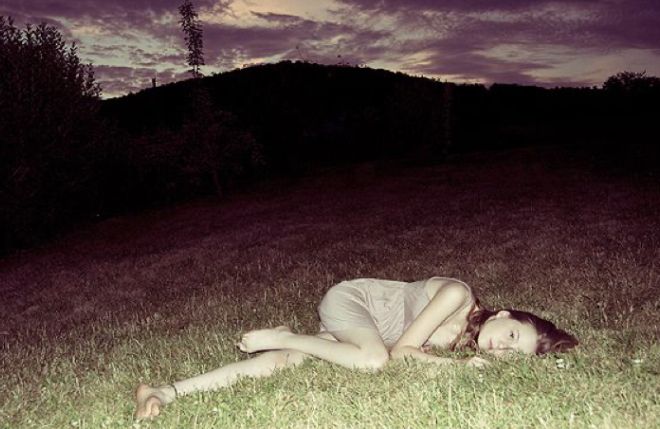

I was face up on a very damp bed of grass on a late September night. I had been egregious for a few egregiously long weeks, and I came down for the thousandth time there, but then by my friend Clea. I cry tons. It’s in my nature. So I was doing that and trying to articulate how afraid I felt of my own feeling. And there was a nausea, a tightening of the chest, a soreness of the shoulders, an incoherence, and a staticky erasure of the breath I know very well. I get myself there so easily these days. I failed to gloss over completely and questioned the sky and its constellations like distant baby’s breath—is it really that, Orion, so early in the fall? Clea deals with me and knows I have a ruminative problem. Once I’d shushed myself and the night went as silent as it could with all the air and insects, and Clea remarked, in attempted assurance, “You are just a speck on the earth, look, just in front of us, the cosmos is so vast, none of this really matters.”

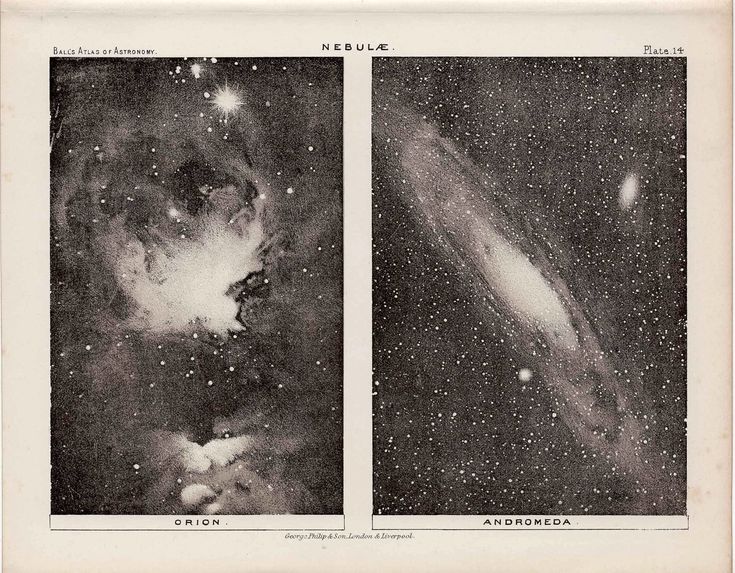

Orion and Andromeda.

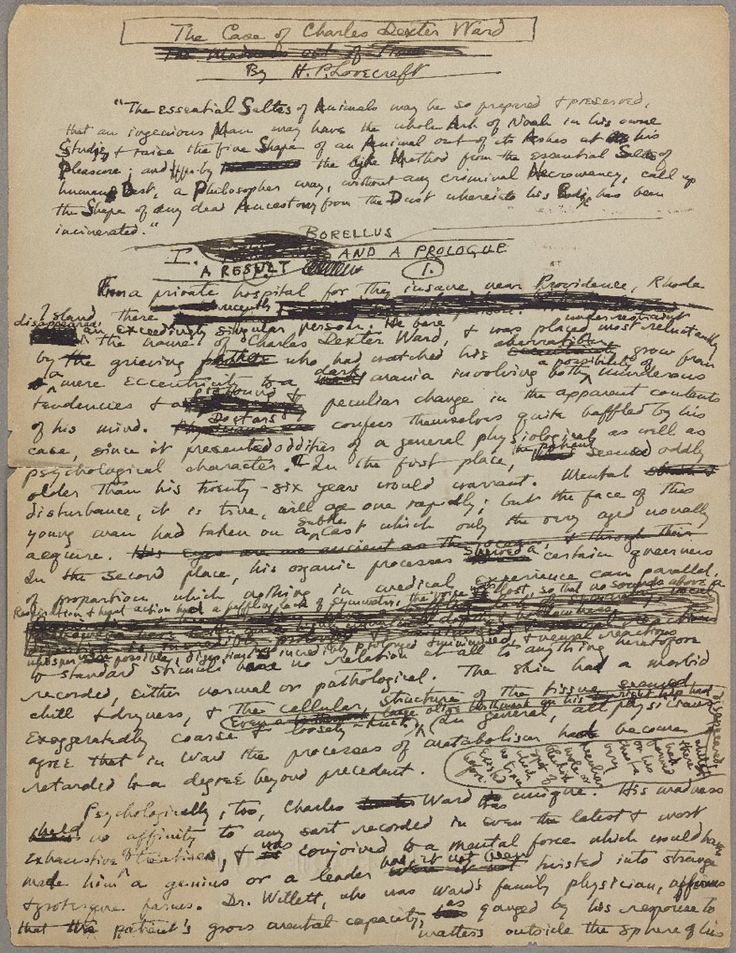

She was likely introduced to this logic by a social media post, as its digital potency has grown over the past few years. She doesn’t live by it or honestly believe in it, but sees it as a mildly comforting or relieving thought. One thing I’ll say is that I love Clea, and would not dare love her less for offering me this—I am just not a manipulative writer, or—I am calling a spade a spade. The other thing I’ll say is that this Instagram-like notion is a fair fragment of a literary philosophy called cosmicism, developed and spread by American author H. P. Lovecraft throughout his career in the early 1920s and 1930s. Put simply by Trung Nguyen, cosmicism posits that “there is no recognizable divine presence, such as a god, in the universe, and that humans are particularly insignificant in the larger scheme of intergalactic existence.” Cosmicism overlaps with nihilism in certain ways, but rather than outright denying the possibility of higher meaning, it highlights humanity’s infinitesimal and powerless nature within the universe. In Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos, for instance, the terror specifically stems from the realization that people are incapable of influencing the immense, indifferent cosmos around them. Any purpose that might exist lies within the motives of the cosmic entities themselves, yet such motives remain eternally beyond human comprehension.

(1) Original manuscript for “The Case of Charles Dexter Ward” by H. P. Lovecraft. (2) H. P. Lovecraft and Sonia Greene.

These philosophies in their purest forms are extreme. They are ways of acknowledging an absolute nothingness that exists but is more overwhelming for some than others. You think of nihilism and then of that overwhelmed some, perhaps Nietzsche, Stirner, Mainländer. Or you think of the mere band-tee-wearing, hand-rolled-cigarette-smoking student who self-proclaimed himself a nihilist mid-conversation with you in a fraternity basement. To me, this is someone who might believe in and understand nihilist principles but bends and selects them, as well as what they might require from their life. They might compartmentalize their belief to dwell on sporadically, when it feels especially true, or compartmentalize their understanding to explain or monologue colloquially—what might have followed in the prior scene. And this is natural and expected in life, because do the deeply affected some exist outside of moody writing rooms, asylums, or coffins? I know that if it were my belief and I couldn’t compartmentalize it, I would end up in one of the three very quickly. But aren’t these compartmentalizations inherently contradictory? The Basement Boy compartmentalizes his nihilism in order to internship hunt (he silences it) and justify the weed fog obscuring his dorm room (he nods to the nothingness). Clea compartmentalizes her cosmicism in order to study for four trembling hours before her calculus test (it’s muted here) and brush it off if she doesn’t reap the A, or to console me on those late September nights, dampened by tears and mildew (then the backslash lifts off of the volume emblem). So, perhaps in this context, compartmentalization and contradiction are complementary; instead, compartmentalization allows for the avoidance of utter contradiction—the philosophy shines when it suits the instant and dims when it doesn’t. Perhaps this is survival—most of us will always be like Clea and the boy—inviting just the fair fragments we can manage. However, this survival tactic has become an onanistic internet iteration. And though the affectedness of the iterators isn’t a concern, its pervasiveness is spurring a spiraling harm.

Basement Boy is very Kyle. Very baller, very anarchist. (Lady Bird, 2017)

Surely, “it’s not that deep,” though. At least, that’s the notion being regurgitated all over the internet. The combined number of videos using “#itsnotthatdeep” and “#notthatdeep” exceeds 25.3 thousand, which is underwhelming and underrepresentative of how common this language has become. I solemnly believe that anyone who has used TikTok or Instagram regularly over the past few years would affirm they’ve seen it on multiple, if not myriad, occasions. The more specific thought Clea had offered me—“we are just a tiny speck in the universe,” or “we live on a floating rock,” so “does it really matter?”—is almost as pervasive but more compartmentally cosmicist than nihilistic. The videos advocating for this logic often depict a human and rapidly zoom out into the cosmos from that “speck.”But the people parroting the philosophy aren’t Camus, articulating its profundity in a Château, they aren’t arsonists, and they aren’t leaping off of the Golden Gate Bridge. They are probably settling for half credit on a late assignment and then studying for the exam the following week. They’re hitting and hiding a spearmint vape, then eating their vegetables, partying, then protecting a friend who needed to cap the night in the bathroom with their hair held back. In a lived sense, this compartmentalization is the same kind of survival tactic that Clea and the Basement Boy practice, so perhaps on an individual level, it is harmless. So why is it intensely harmful as an internet iteration, and in what way?

The Château de Lourmarin is located in the village of Lourmarin, in the Luberon region of Provence. Camus lived in Lourmarin and found solace and inspiration in the village. He is buried in the village cemetery.

The logic is being used to deride and dismiss on a vast scale, but most noticeably targets activism, criticism, intellectualism, humanitarianism, emotional expression, and introspection, ultimately nourishing an unbridled ignorance. You’ll see it in the comment section of a clip featuring Greta Thunberg, of a slideshow examining the symbolism of marigolds in The Bluest Eye. Or in text over a video attempting to dull claims of fascist behavior from the US administration, over a montage of clubbing photos to a song from the Saltburn soundtrack. It cascades—dismissing activism as hysteria, antagonizing critical thought and erudition as pretentiousness. It undermines humanitarianism by mocking the intensity of care and trivializes emotional expression and introspection by casting them as overreactions. In this way, the pervasiveness isn’t detrimental because anyone suddenly believes in nothing, but because indifference has become ambient. The language can individually help people manage the instability of meaning, but now that it has leaked outward online and has an atmospheric presence, it’s as if detachment and rationality are synonymous. It doesn’t erase conviction so much as make it seem slightly embarrassing, a sign of naivety or overinvestment. It has become a way of staying untouched, and the result is a culture fluent in deflection.

It is not that I have never questioned the meaning of anything, though. It is just that when I do, it affects me in a different way than it does for Clea, Basement Boy, or any of the internet iterators. For me, it’s completely disorienting, and frankly depressing. According to my friends and family, I am someone who cares and feels too much, thinks and tries too hard, and has a corrosively contemplative, overanalytical, self-critical, ruminative problem. I see meaning in nearly everything, and when I don’t, I search for it. Sometimes, it does become irrational, and I can fully recognize that. For instance, there was a time when I cried myself to sleep for two weeks over how I felt about my conclusion on a timed writing assignment. The morning after that writing, I was taking the SAT and could barely focus because of how shameful I felt. I convinced myself that I was the dumbest, most underperforming student in the world and was in dire need of medication, all to end up receiving a respectable grade on the piece (though that didn’t make me feel much better). I don’t think that the intensity of this quality is admirable or anything to aspire to, but it is merely the way I am, and this is true for a considerable number of people. So, when I do find myself questioning the meaning of something, it quickly becomes a questioning of the meaning in anything; in myself. This is more a headspace of helplessness than humility—as I don’t care about my inherent importance as much as I care about my capacity to contribute to important things. So when am having one of these overwhelming episodes, considering the way I am living and doing and if it is right or worth anything, in this case, by Clea on the wet grass, her preposition that again, I am “just a speck” within the unbounded universe and that nothing matters in light of its indifference, I am going to panic. I shiver all over; this is not at all comforting. Because, of course, I do not matter, but if what I do does not matter, then why should I do or be anything at all?

Nebulosities of the Pleiades.

The only philosophy that has been able to ground me in this dread belongs to Clarice Lispector, “one of the hidden geniuses of the twentieth century,” Colm Tóibín rightfully contended. A mere seven pages in to Lispector’s Água Viva, I was flushed with an unfamiliar okayness, reading and re-reading her words: “I’m growing with the day that as it grows kills in me a certain vague hope and forces me to look at the hard sun straight in the face. The gale blows and scatters my papers. I hear that wind of cries, the death rattle of a bird open in oblique flight. And here I impose upon myself the severity of a taut language, I impose upon myself the nakedness of a white skeleton free of humours. But the skeleton is free of life and while I live I shudder all over. I won’t reach the final nakedness. And I still don’t want it, apparently. This is life seen by life. I may not have meaning but it is the same lack of meaning that the pulsing vein has. I want to write to you like someone learning. I photograph each instant. I deepen the words as if I were painting, more than an object, its shadow. I don’t want to ask why, you can always ask why and get no answer—I could manage to surrender to the expectant silence that follows a question without an answer? Though I sense that in some place or time the great answer for me does exist. And then I shall know how to paint and write, after the strange but intimate answer. Listen to me, listen to the silence. What I say to you is never what I say to you but something else instead. It captures the thing that escapes me and yet I live from it and am above a shining darkness. One instant leads me numbly to the next and the athematic theme unfurls without a plan but geometric like the successive shapes in a kaleidoscope. I slowly enter my gift to myself, splendor ripped open by the final song that seems to be the first. I enter the writing slowly as I once entered painting. It is a world tangled up in creepers, syllables, woodbine, colors and words—threshold of an ancestral cavern that is the womb of the world and from it I shall be born.”

Clarice Lispector.

Lispector begins by acknowledging the interchangeability of life and death, remarking that the day’s expansion doesn’t nourish but burns away a “vague hope,” forcing her to confront “the hard sun” directly. This is cosmicism’s position too—the growth of knowledge kills solacing illusions, leaving only the hard face of the indifferent universe. But unlike the internet’s “floating rock” rhetoric, the confrontation isn’t embellished. It is severe and unwanted. Lispector then tries to discipline herself into philosophical austerity, “the nakedness of a white skeleton free of humours.” But she recognizes that the skeleton is lifeless; to be alive is to “shudder all over,” to resist the austerity of the “final nakedness.” This is a direct rebuke to the impulse to shrink everything into a comfort—she isn’t compartmentalizing or surrendering, and is holding in the entropic turbulence of life and thought. She faces the same cosmic smallness implied by “we are but a speck on the universe,” but refuses both to collapse under it and to make it palatable. And then, what struck me most forcefully: “I may not have meaning but it is the same lack of meaning that the pulsing vein has.” She reinterprets the “lack of meaning” I feared as a void as a life-force. A vein doesn’t have a grand “meaning,” but it pulses as the beating heart does and therefore is “the most profound thought.” Life continues and insists upon itself and its significance because, without it, there is no consciousness to recognize anything else. Lispector shows commitment to presence over deflection, wanting to write “like someone learning,” to “photograph each instant.” She’s willing to ask and suffer answerless questions, and “deepen the words as if [she] were painting, more than an object, its shadow.” Even while acknowledging chaos and darkness, she understands it to be generative rather than numbing, calling it “shining” and “ancestral,” the “womb of the world.” This is the same cosmic indifference that cosmicism describes, which agonized me, that the internet is solaced by, and that is being used to shush pain, but also passion, and then life. Lispector offers the clearest response to it: without any guarantee from above, seriousness can only come from what we extend—attention, accountability, tenderness.

The Hour of the Star.

It is okay for Clea to study tediously for that exam, for Basement Boy to anxiously edit his LinkedIn every other day. It is okay for me to ridicule myself over my uninsightful timed conclusion paragraph, to voraciously annotate Duras and Zweig, to tear up with a dolorus emotion each time I see images of emaciated children in Gaza. It is not that there’s nothing that matters; rather, there is nothing without mattering. It is scientifically accurate that I am but a speck on the universe, but a speck of what, mind you?—a speck of life. I find that there is nothing I can or want to do but live for the life streaming to and from myself and the other specks on the floating rock—and know it is worth something because it is the only thing. And if this is all there is—no guarantee, no cosmic consequence—those qualities I mentioned are essential. Attention separates human life from the compartmental-cosmicist take on nothingness; accountability is self-imposed gravity, and tenderness is a nerve or sensitivity left intact. Holding onto these things steadfastly is the work of living within the indifferent cosmos.

Basicalement.

So back on the grass, mildly soaked for the two reasons I’ve repeated, I did end up squinting well enough to realize it was Orion, nearly out of season. I know him as the hunter and the anciently wise—understanding cosmic order, the wonder of animalistic forces in humanity, the divine truths beyond our comprehension. He shines but does not share his knowledge. I think of another string of Lispector’s words: “In the beyond of my thought is the truth that is that of the world. The illogicality of nature. What silence.” What I’ve begun to understand is that silence and its impenetrable equivocacy are livable beyond survivability. I turned over with my bodily force and felt the misty grass dampen my skin, my skin against the earth, enveloped by the cosmos and still right beside my dearest friend Clea, hearing the unlabored beating of our childlike hearts.

Leave a comment